AL WATAN AL ARABI

Walid Abou Zahr settled in Paris after a short passage in London. There his mind couldn’t stop brewing on how to publish a newspaper. It’s only when he met his brother Ziad that he took the decision to resume his passion. His brother told him “No hesitation, you must start now” and so he did.

Al Watan Al Arabi (The Arab Homeland) was launched in February 1977, as the first pan Arab magazine to be based out of Europe. Its aim was to become the platform of all the Arabs in the world. A strong voice defending Arab causes and denouncing the abuses of powerful forces.

The magazine also played an important cultural role, as it opened its pages to the intellectuals of the Maghreb and Europe, at the time when the Levant and Gulf’s readers did not hear the names of many of them. The weekly supported and helped Arab immigrants on the five continents and offered them a comprehensive guide to help them integrate and understand the laws and regulations of the country that was hosting them. The magazine was faithful to the name it carried, The Arab Homeland.

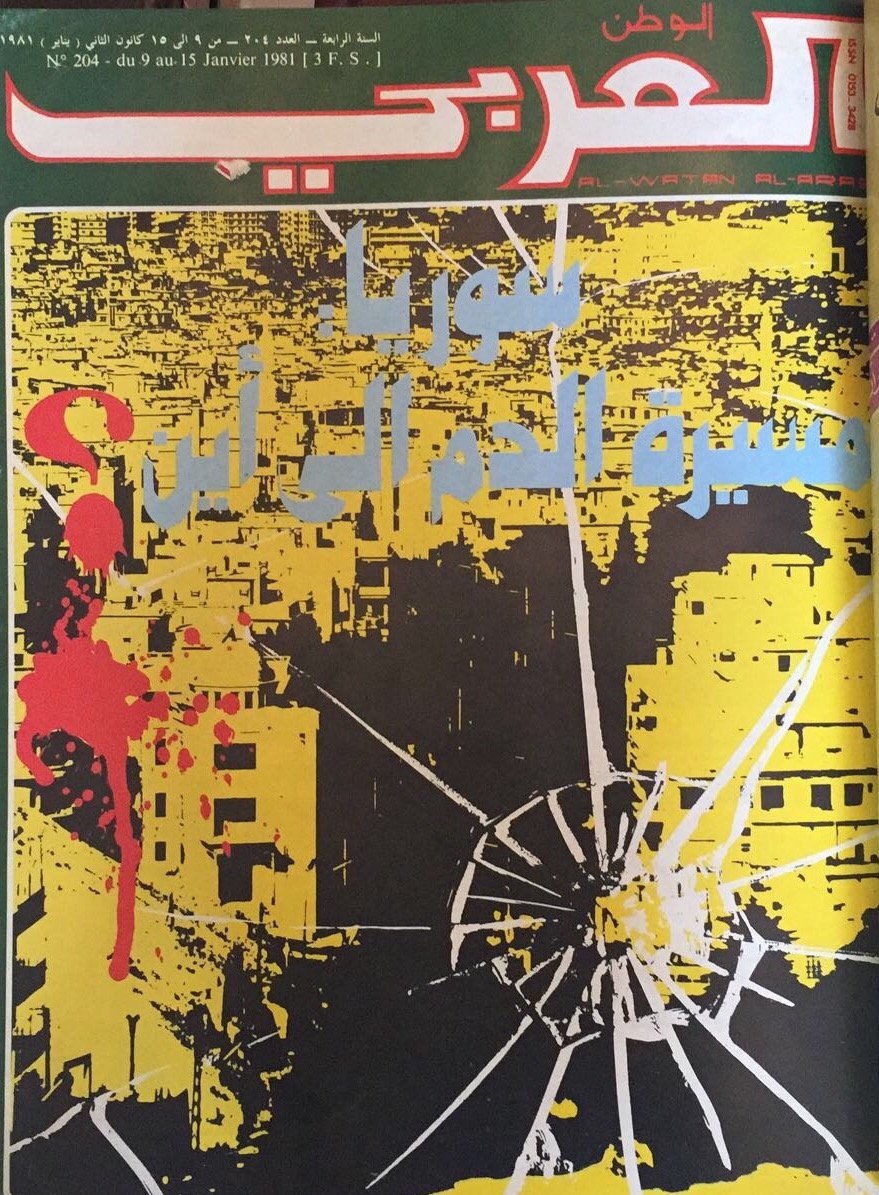

Al Watan Al Arabi was an extension of Al Moharrer and shared its very same spirit. The magazine therefor took a strong line against the Assad regime, giving plenty of space to Syrian opposition leaders. As a result, Walid Abou Zahr collected death threats. In 1979, he narrowly escaped being stabbed to death when a gang of assassins armed with knives mistook a neighbor for Walid Abou Zahr and attacked him. The neighbor survived.

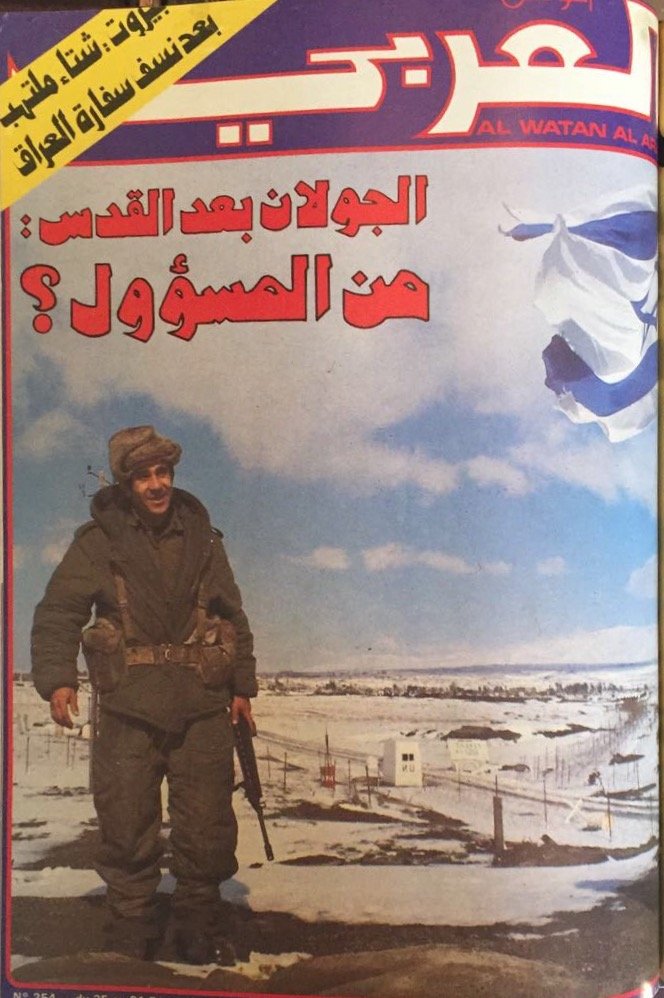

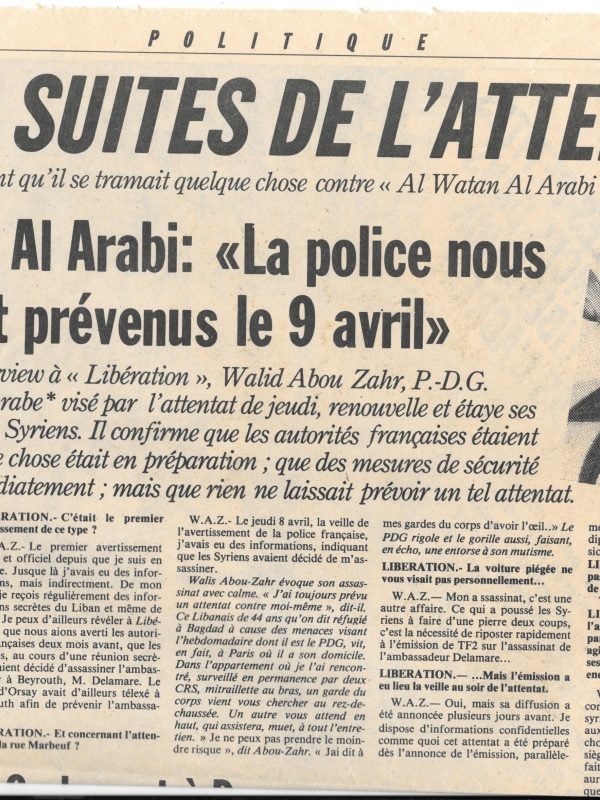

His fight for the Arab causes and opposition to the Syrian regime invasion of Lebanon made him a target for assassination. Among its many scoops, Al Watan Al Arabi revealed the plans for the assassination of the French Ambassador to Lebanon by the Syrian secret services. In September 1981, the Ambassador was kidnaped and cowardly assassinated confirming the published scoop. A few months later December 1981, a bomb hidden inside a radio box at the doorsteps of the offices of the magazine was defused in extremis.

This didn’t stop Walid Abou Zahr and the magazine maintained its same independent editorial drive.

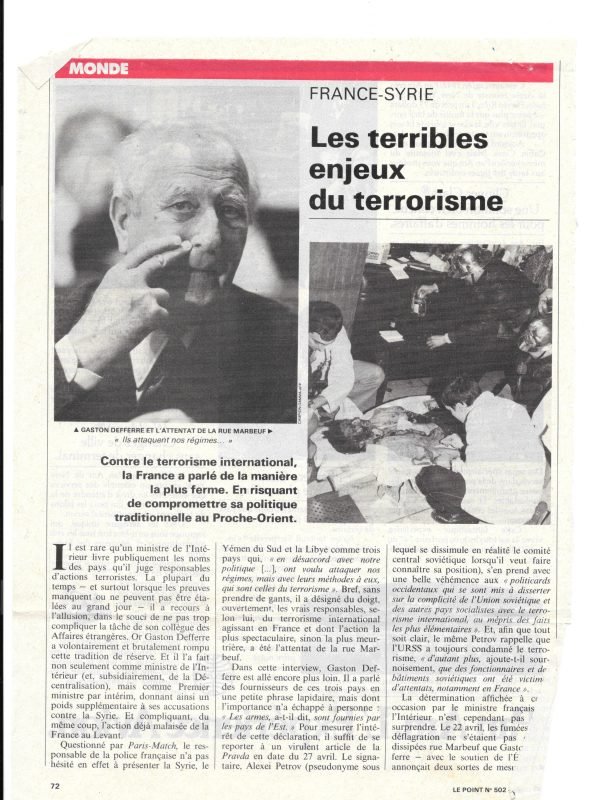

Early 1982, TF1 was planning to run a documentary of this murder. The Syrian intelligence decided at that time to target Al Watan Al Arabi and its owner. Syria wanted to destroy and silence the magazine and warn against dabbling in Syria’s Lebanese back yard after President Mitterrand demanded that foreign powers leave Lebanon in peace.

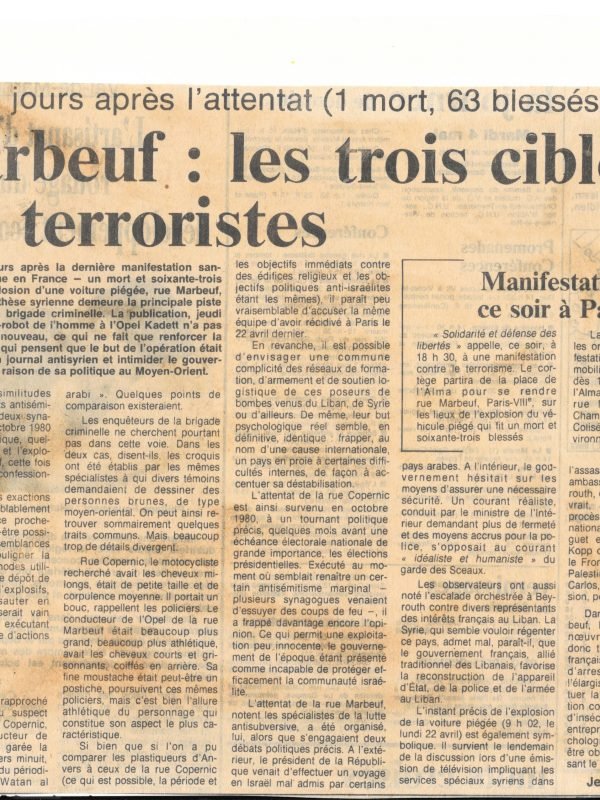

In April, Walid Abou Zahr was told by an Arab informer that a thirty-strong Syrian unit had arrived in Paris and was planning an attack. But the informed did not know what the target was. Abou Zahr increased his security surrounding himself with nine bodyguards.

On April 21, French television TF1 broadcasted the documentary on the murder of Ambassador Delamare. The program relayed the accusations against the Syrian secret services made by Al Watan Al Arabi.

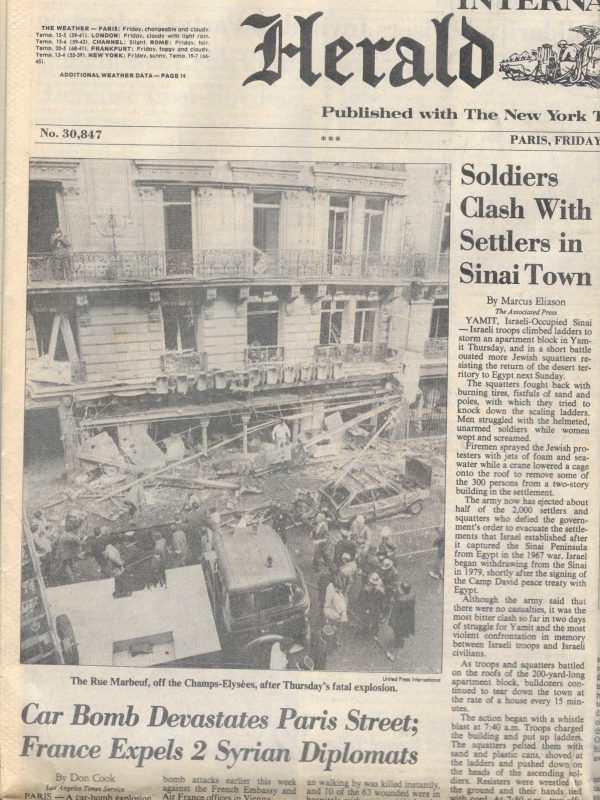

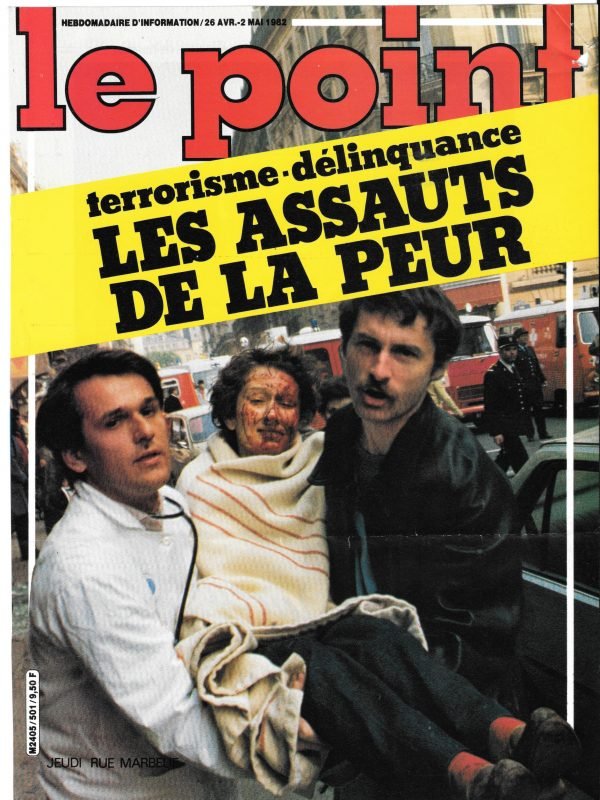

On April 22, at 9.02 a.m., a twenty-kilo bomb hidden in the back of an Opel station wagon exploded in front of the offices of Al Watan Al Arabi rue Marbeuf. This attack killed Nelly Guillerme an innocent woman. The bomb ripped through the street wounding 68 people. Later this year, French authorities expelled two Syrian diplomats.

These attempts didn’t change the editorial guideline of the magazine which kept fighting against the presence of Syrian troops in Lebanon.

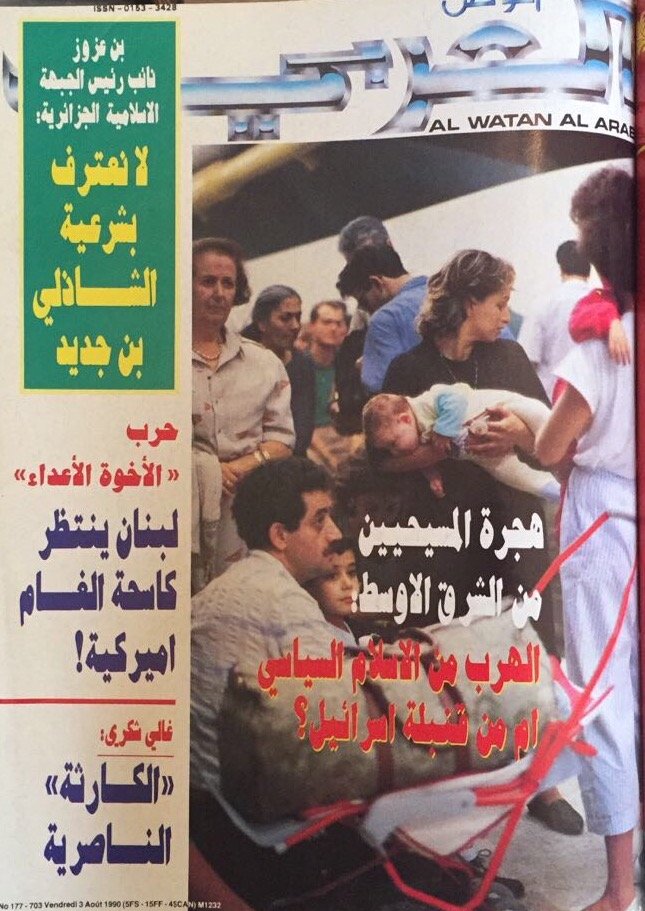

Walid Abou Zahr was a great supporter of Iraq during the war against Iran and stood against the Iranian export of the Islamic revolution to Arab countries. His strong editorials and impactful magazine covers that always defended and promoted Arab Nationalism have contributed in changing political views in entire countries that were fascinated by the new Islamic experience in Iran. An Algerian Minister once said to Saddam Hussein openly “You should build this man a gold statue, he completely changed the support of the Algerian people from Iran to Iraq through his magazine”. When Saddam Hussein told the story to Walid Abou Zahr; he answered with his well-known sense of humor: “Keep the statue, give me the gold”.

Yet as the Iran-Iraq war was coming to an end; the relation between Al Watan Al Arabi and Iraq was shook when the Iraqi intelligence headed by Saddam’s brother, Barzan Al Tikriti tried to take over the magazine. They offered Walid Abou Zahr the set-up of a USD500 million international conglomerate; ranging from construction to energy for Iraqi interests in Lebanon and the world and in which the media company would be a part of. As he was growing uncomfortable with the Iraqi regime policies and because his independence was his most valuable possession; Walid Abou Zahr declined the offer, refusing to become a puppet in the hands of any regime.

He knew what the consequences would be: all distribution and financial dues from Iraq were blocked. This came at a time when all influential Pan-Arab Lebanese independent publishers were being squeezed out because regional governments had started to establish their own European-based media outlets. It is during this period that Al Mustakbal magazine a competing title went bankrupt and others were taken over as well as shut down and replaced by government owned news outlets.

Despite an extremely difficult financial situation, Walid Abou Zahr was able to keep sail and continued to publish his own opinion. It’s then that he established his first presence in Egypt, a country that was still isolated due to the signing of the Camp David agreement with Israel.

In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. He couldn’t accept that what had been done to his beloved Lebanon by the Syrian regime be replicated by the Iraqi regime in Kuwait and so he condemned this invasion. That stand marked the end of his ties and historical friendship with Iraq and came with huge financial losses as the magazine lost all its dues in the country. Additionally, Walid Abou Zahr couldn’t stand against King Salman Bin Abdelazziz who was governor of Riyadh at the time and who had always shown his support and appreciation.

After the first Gulf war, the region had changed and Walid Abou Zahr entered a wiser phase in his journalistic life. His tone became less aggressive and his focus more on policy making. He was now writing to promote change in the region through dialogue and self-analysis.

Still, some enemies never forgot and in 1992 an armed robbery was organized in his Parisian home while Walid Abou Zahr had travelled the night before on a last-minute business trip to Egypt. His wife and son and one of his daughters were held at gunpoint by 3 masked men who had subdued the security of the building. Up until this day, no one knows whether this was a last attempt on his life or a final warning.

In the last decade of his life, media still played an important part in Abou Zahr’s life with more scoops and more achievements. The first interview of Israeli Prime Minister Itzhak Rabin was published in Al Watan Al Arabi as the peace process was revived. Also, with the help of his children he developed a full family of titles that are still well renowned in the region.

For Walid Abou Zahr, the complex story of Al Watan Al Arabi is the story of the Arab homeland; despite the dangers, the plots and the wars, it remains resilient.